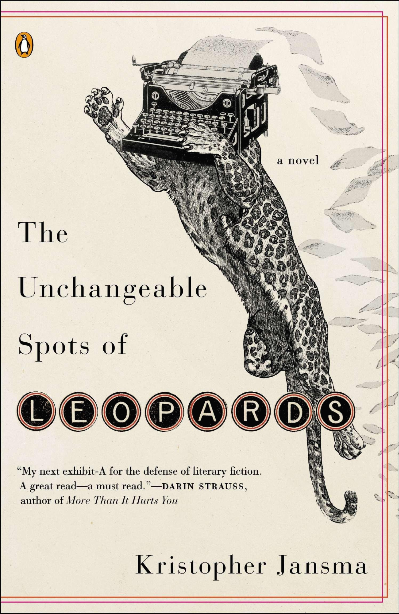

5년 가까이 to-reads 리스트에 묵혀만 놨다가 읽었기에 기대가 많이 컸던 소설이다. 중반부까지도 기대 이상의 흥미진진한 전개를 보여줬지만 후반부로 갈수록 이야기의 긴장감이 풀리면서 끔찍하리만치 지루했다. 백인 남성이 제3세계 문화에 대해 지나치게 낭만화하고 여자 뮤즈 클리셰 나오는 것도 거슬렸고 그냥... 정말로 후반부부터는 읽는 것 자체가 고문으로 느껴질 정도로 재미가 없었다.

"F. Scott Fitzgerald meets Wes Anderson"이라는 평에 끌려서 읽고 싶어했던 소설인데 확실히 피츠제럴드와 웨스 앤더슨을 섞은 느낌은 난다. 여하튼 딱 중반부까지만 재미있는 소설이었음.

I listened intently, for I had never set foot in Terminal A. My mother never flew internationally and did not know anyone willing to look after me over there. I had dreamed about Terminal A many times. I imagined it to be just the same as Terminal B, but in reverse—a looking-glass terminal, where everyone did everything backward. Or, if it was A, and we were B, perhaps it was the original and we were the copy. Perhaps I was only a reverse version of some other boy whose life was the other way around.

“Each time it goes around a little bit, a second goes away.” “Where?” I asked, as the pendulum swung again. And again. He winked at me. “It escapes. That’s why they call it that. Escapement.”

She was amused, I was sure. Only, rather than smile, she somehow un-smiled. Then I saw it at last: Betsy’s smile was the absence of smiling.

“I’ll hide you in the café. I can make you a Viennese hot chocolate.” “Vell, can ve keep talkink about mein pater, Herr Freud?” “Vhat better place?” I replied, scratching my imaginary goatee. “Ve’ve even got a little couch you can lie on.”

Then he fumbled with his wallet until he pulled out a crinkled newspaper review for a musical called Samson!, and at the top was a picture of her on stage as Delilah, in sheer crimson silk. Even on smudgy newsprint, she was stunning. Slender and high cheeked, with hair tied up in a perfect knot. I could not look away. Her eyes seemed to bore right into me, and somehow she looked bored herself, by what she found there.

This seemed to be Julian’s philosophy on life: that no one could ever hope to get the breadth of the whole thing, so he would stick to the extremes and assume the middle was thus covered.

Julian held books right up close to his face—a habit formed, he explained, in his nearsighted youth—and now, even with contact lenses in, he liked to have the page within a few inches of his eyes. So close that the pages scraped the tip of his nose as he turned them. So close that, when he inhaled sharply at a particularly good turn of phrase, the paper seemed to lift up slightly and tremble before settling back again.

She looked at everything like it was a sad, small version of something better she’d seen somewhere else. It was how she looked at me.

Evelyn always says that when she thinks about me sitting there in the front row she becomes afraid of losing her character. She says it would simply be the end of her. So I never tell her which shows I am coming to, and I sit back beneath the dark underhang of the mezzanine with a set of Julian’s opera glasses and my heirloom roses, and I watch, and I wait.

But though Anton’s face was white as the snow outside, he stayed put. His eyes followed every motion, each slice. As he inhaled the oily stink of the fish, I saw his lips moving slightly, choosing words, testing phrases, timing cadences. He was writing the scene, already. Immediately, I felt my own pulse quickening. I wanted it, too. Here it was—right in front of me, the end of a much better story than the one I had lost. The story of how I’d lost the story.

Somewhere, once, I read that the only mind a writer can’t see into is the mind of a better writer. When I watched Julian watching the world, I was always reminded of this.

And last week, there’d been the disappearance of Mrs. Menick’s always-barking shih tzu puppy. There’d been the scratch marks on Julian’s left arm. And then a cabbie had found “Shihtzy” a day or two later, outside Hempstead, Long Island. The dog was doing just fine now, except that she had yet to emit even a single bark or whimper since her disappearance.

Any time of day, even in commercial breaks, the students could identify an endless stream of manipulation. The truth is bent constantly into lies—right before our very eyes and ears, every day of our lives, and they are hip to this fact. Change the channel to MTV and they can see their idols doing the same thing: pop singers who reinvent themselves to seem like the girl next door in one interview and little better than porn stars in the video that follows. Or rappers who back their words with claims of rough streets, so we’ll forget their bank account balances are in the triple millions. And the students idolize these frauds. They dress like them and speak like them because they’re frauds. They’re heroes because they’re good frauds. And the students then reinvent themselves as ever-better miniatures of their fraudulent role models.

Maybe an idea, like love, cannot ever be stolen away, just as it cannot ever have belonged to me and only me.

“My grandmother tells me you have your thought-soul and your life-soul. When you die, the life-soul goes away. But your thought-soul sometimes it stays here for a few years. But sooner or later it goes away, too.” I chew this over. It is growing darker and the city is still some distance away. “Can the two ever split up while you’re still alive?” “If you are in danger,” he says, nodding, “your life-soul may go away and hide. And if then, you are hurt or wounded, you will still not be killed. And then, when you are better, it will come back again.”

“When Percy died,” she says at last, “they burned him on a pyre by the sea. Only a disturbed fan came rushing up and into the fire. People thought he was insane—trying to die with him, or something. But then he rolled away, all burned and on fire, with Percy’s heart in his hand. He rushed off before anyone could stop him.” “Crazy,” I say. “That’s not even the crazy part. Because years later, when Mary died, they found a little parcel in her desk. One of his original drafts of Adonaïs, his elegy for Keats, and wrapped up in it, this withered, burned-up lump of Percy’s heart.”

I want to live and every morning I want to write something that’s worth wrapping my heart in when I die.

And for this imperfect immortality, what prices have been paid? How many livers, lungs, and veins? Shredded, polluted, shot? How many children deserted, family secrets betrayed, sordid trysts laid out for strangers to see? How many wives and husbands shoved to the side? How many ovens scorched with our hair? Gun barrels slid between our lips? Bathtubs slowly reddened by our blood and twisting rivers that drowned us?

“‘A book must be the ax for the frozen sea within us,’” Jeffrey says sagely. “That’s lovely,” I say. And I mean it. “Kafka,” he says proudly.

Do not trouble yourself much to get new things, whether clothes or friends. Turn the old; return to them. Things do not change; we change. —HENRY DAVID THOREAU, WALDEN

“You don’t understand! I’ve known her since she was thirteen years old! We went to school together! In America? Ah-MER-Ik-KAH. For chrissakes, this one’s slept with her more times than you all have been invaded by Germany.” I thanked any and all available gods—including the one who had toppled the Tower of Babel—that this last bit seemed to get lost in translation.

“Menger Meenung no hunn si sech nach net geréiert,” she stage whispers. Jeffrey and I exchange a brief look. It had not occurred to either of us that the play, like the newspapers and the books and the television, would be in Luxembourgish.

'독서' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 목소리를 드릴게요 / 정세랑 (0) | 2020.01.31 |

|---|---|

| Horns / Joe Hill (0) | 2020.01.05 |

| 2019. 08 독서 (0) | 2019.08.31 |

| 조선 여성 첫 세계 일주기 / 나혜석 (0) | 2019.08.31 |

| To Kill a Mockingbird / Harper Lee (0) | 2019.07.31 |